Leveraging Player Motivation Models to Increase App Engagement – Part 1

Paula Neves is a Product Manager at Square Enix and describes herself as a gamer turned psychologist turned marketer working in mobile free-to-play games. Prior to joining Square Enix based in Montreal, Paula was the Chief Mobile Officer at Gazeus Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where she headed up user acquisition and product management. Paula is a proud member of the UA Society and a frequent speaker at industry events and conferences, where she eagerly shares her knowledge and experience from her 10+ years in the mobile app marketing industry.

Learn more about Paula from her Mobile Hero profile.

This is the first part of a three-part blog series intended to explain what motivates players into picking up a game and continuing to play it. It’s a combination of psychology models transposed into gaming and its characteristics. This blog series hopes to educate product managers, marketers and game designers on player psychology and how we can all leverage it to make a game that more people will play. You can read part two of the series here and part three of the series here.

As an undergraduate in Psychology, a graduate in Marketing and a professional in the gaming industry, I’ve always tried to combine what I learned in college with what I do at work. Psychology and marketing go hand in hand, especially when it comes to designing games, and even more so when they’re Free-to-play.

In Free-to-play games, most systems and mechanics are built on the principles of behavioral psychology and we hear a lot about theories like risk aversion, reciprocity, endowment, and the like. But when it comes to planning your next game, for a long time I felt that our industry was missing a good game design framework that is built on science and psychology. That was until six years ago when I first heard of Scott Rigby and his work at Immersyve, and the guys at Quantic Foundry. I started going down the rabbit hole, coming across several interesting player motivation models that all have a recognizable psychology framework as a foundation, like the work done by Jason Vandenberghe and his Domains of Play and Ethan Levy and his Tower of Want.

This is the first part of a three-part blog series intended to explain what motivates players into picking up a game and continuing to play it. It’s a combination of psychology models transposed into gaming and its characteristics. This blog hopes to educate product managers, marketers and game designers on player psychology and how we can all leverage it to make a game that more people will play. Thankfully, this work is already being done by the people I mentioned earlier, so my intention here is to put it all together so that the knowledge is accessible to others.

Self Determination Theory and Long-term Satisfaction

The Self Determination Theory (SDT) is a psychological theory of human motivation that addresses three basic psychological needs including:

- Competence: the need to experience mastery, growth and learning, and to feel successful and effective.

- Autonomy: the need to feel that you’re in control of your choices and in harmony with your decision. In games, it translates to choice, customization and agency.

- Relatedness: the need to be cared for and to care for, to be connected with others, knowing that you belong and matter.

According to the theory, these needs are innate, universal to everyone, and if met, will lead to self-motivation and growth. The theory also makes a clear distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivations: The former being caused by external factors, such as being paid to do your job or being made to feel guilty about not doing something. When said guilt — an external factor — motivates you to do something, that behavior is not self-determined. Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is when one feels inwardly motivated to achieve something in order to satisfy things like autonomy and competence.

For quite some time extrinsic motivation was judged as bad and intrinsic as good, but it isn’t so black and white. It’s almost impossible to have something — like a game — that will only motivate players intrinsically. As a game designer you must try to kindle more intrinsic than extrinsic motivations, but some extrinsic motivations, like giving rewards for completing actions, are unavoidable and not always bad. If you have an external goal that you identify with, you’ll feel motivated to complete tasks in order to fulfill said goal. That’s a good type of extrinsic motivation.

Self Determination Theory and Video Games

Scott Rigby and the people of Immersyve used SDT as a foundation for their own model: The Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS). The team studied over 7,500 players and their motivations to continue a game for a prolonged period of time and found that PENS had a strong correlation with what compelled players to not only play a game for months and years on end but to identify as a [insert game name] player. I’m a DOTA player.

The basic needs as described by SDT can translate into gaming as such:

Competence

A game is easy to learn, but difficult to master. First Person Shooters and skill-based games like Super Meat Boy are big on competence need satisfaction.Rigby proposed that in order to satisfy competence, game designers should try to create the optimal level of challenge for the player. He refined this idea through Polish psychologist Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of “Flow” –– a psychological state where one is completely immersed in a task. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi defined “Flow” as:

“…the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.”

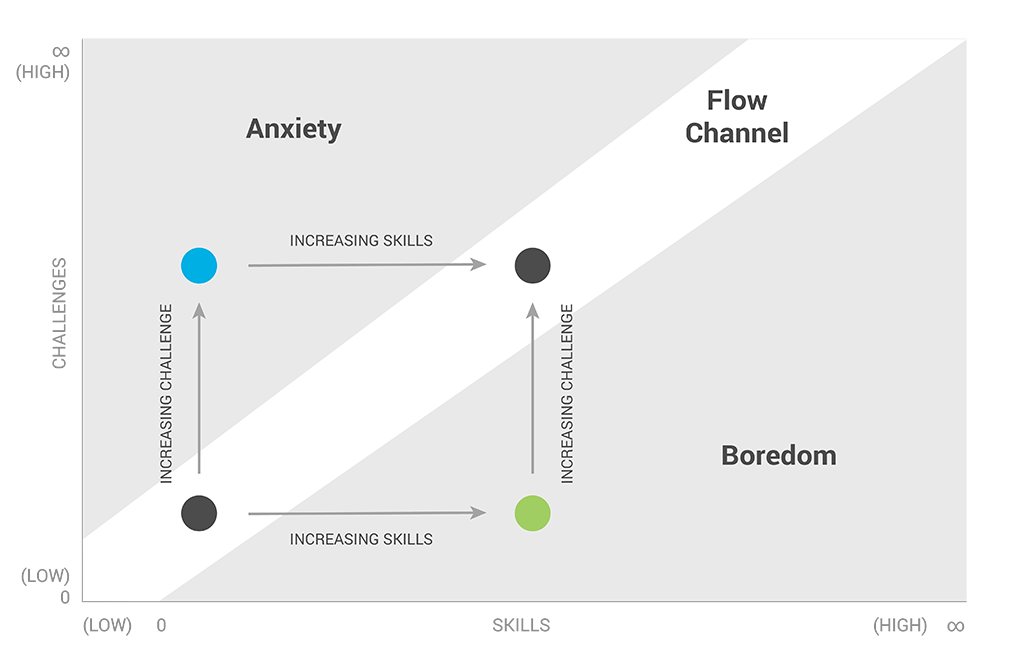

According to Csikszentmihalyi, Flow happens when challenges are appropriately matched to one’s ability. If the task at hand is too simple, people will get bored and not experience Flow. If it’s too challenging, people will get anxious, frustrated, and similarly won’t reach the state of Flow.

Making adjustments to Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of Flow, Rigby believed focusing only on the optimal challenge wasn’t enough. Game designers should concentrate on creating a balanced mastery curve (or difficulty curve) for their games. The curve should be so that challenges presented are slowly more conquerable — because the player is getting better at the game — and provide gamers the possibility to express their mastery. While the optimal challenge was an important element, if the player doesn’t get a chance to progress and convey their mastery in action, then their competence need won’t be satisfied.

In line with player progression, whenever one expresses this mastery, they should receive clear and immediate feedback on their accomplishment. This dictates the importance of over the top animation and feedback design in the user experience.

Autonomy

A game that satisfies players’ needs for autonomy gives them choices, customization and agency. Role-playing games (RPGs) and massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) are usually great at satisfying the autonomy need by maximizing the player’s opportunities for action and giving them an entire open world to explore and character sheets to customize.

Choices that are forced upon us, like invisible walls in a game world, feel weird and are demotivating. Scott Rigby states that it isn’t exactly the act of — for instance — customizing your character that will satisfy autonomy, but rather coming back to your character later and having a feeling that “I created this and it’s awesome.” According to PENS, autonomy is particularly important for titles that achieve a perennial value for players, those that are played for years and define their players’ identities. In his research he found that first-person shooter (FPS) titles — more commonly known for creating competence need satisfaction — also satisfy the need for autonomy.

Relatedness

Satisfying the need for relatedness is possible through features such as social grouping and status feedback systems. MMOs and multiplayer online battle arenas (MOBAs) are big on relatedness need satisfaction because they provide a strong sense of belonging through parties and guilds. In these games, you’re always looking after your party and you are looked after by them.

Relatedness is commonly thought of as “the social need” and often, mistakenly, thought of as pertaining only to multiplayer titles. However, non-player characters (NPCs) can be a big driver of relatedness where, when scripted properly, players end up having an emotional connection to that character. Anyone who played Fallout 4 probably related to Dogmeat, the NPC dog that accompanies you in your travels through the wasteland.

Conclusion

By focusing on the three basic psychological needs that the SDT model proposes, game developers are creating psychological experiences that form the building blocks of fun and not only fun itself. According to the scientists at Immersyve, this is a preferable approach because fun is “only” the outcome of the experience and therefore an intangible construct.

As game designers and product managers we have to ask ourselves: Does this feature promote competence, autonomy, or relatedness? I found out the practical way (read: the hard way), that game mechanics and systems can either promote or, if not done properly, thwart these three basic needs.

Remember that you don’t have to design all three needs into every little microfeature of your game, but when you look at the macro of that feature — the overarching, big feature — it does have to address the three needs. Maybe a couple of micro-features will address relatedness and another five will have both a combination of competence and autonomy, but when you look at the big picture of the (to use scrum language) Epic feature all three needs should be well represented for that Epic to be successful in the long-term.

This framework helps answer how to keep players engaged and create long-term satisfaction, but does it also explain the motivation behind users’ install and purchase decisions? Why did players install your game to begin with? In part two of this series, we’ll dive into Jason Vandenberghe’s framework, the Domains of Play, and how it helps explain what drives users to install or purchase your game.