Leveraging Player Motivation Models to Increase App Engagement – Part 2

Paula Neves is a Product Manager at Square Enix and describes herself as a gamer turned psychologist turned marketer working in mobile free-to-play games. Prior to joining Square Enix based in Montreal, Paula was the Chief Mobile Officer at Gazeus Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where she headed up user acquisition and product management. Paula is a proud member of the UA Society and a frequent speaker at industry events and conferences, where she eagerly shares her knowledge and experience from her 10+ years in the mobile app marketing industry.

Learn more about Paula on her Mobile Hero profile.

This is the second part of a three-part blog series intended to explain what motivates players into picking up a game and continuing to play it. It’s a combination of psychology models transposed into gaming and its characteristics. This blog series hopes to educate product managers, marketers and game designers on player psychology and how we can all leverage it to make a game that more people will play. You can read part one of the series here and part three of the series here.

Taste versus Satisfaction

In part one, I addressed the Self Determination Theory (SDT) and its application in the Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS) model for games. The model affirms whether particular games fulfill basic psychological needs that result in long-term players. But a begging question lingers: Is there a relationship between a gamer’s preferences and the theory of needs satisfaction?

According to Jason Vandenberghe, the former Creative Director at ArenaNet and Ubisoft, the answer is no. As a strong advocate of applying psychology frameworks within game design, Vandenberghe’s numerous research and playtesting validated a hypothesis: the motivations behind an individual first buying and playing a game are not relevant to the action of playing a game for the long run. Satisfaction is one thing, but taste is another entirely.

On one hand, Vandenberghe discovered that users are guided by individual tastes when choosing what they want to first begin with. However, we are guided by universal satisfactions when determining what we want to continue.With this in mind, Vandenberghe established a new psychological theory with a driver of individual preferences. Rather than determine taste through the SDT, he relied on the Five Factor Model (also known as the Big Five personality traits).

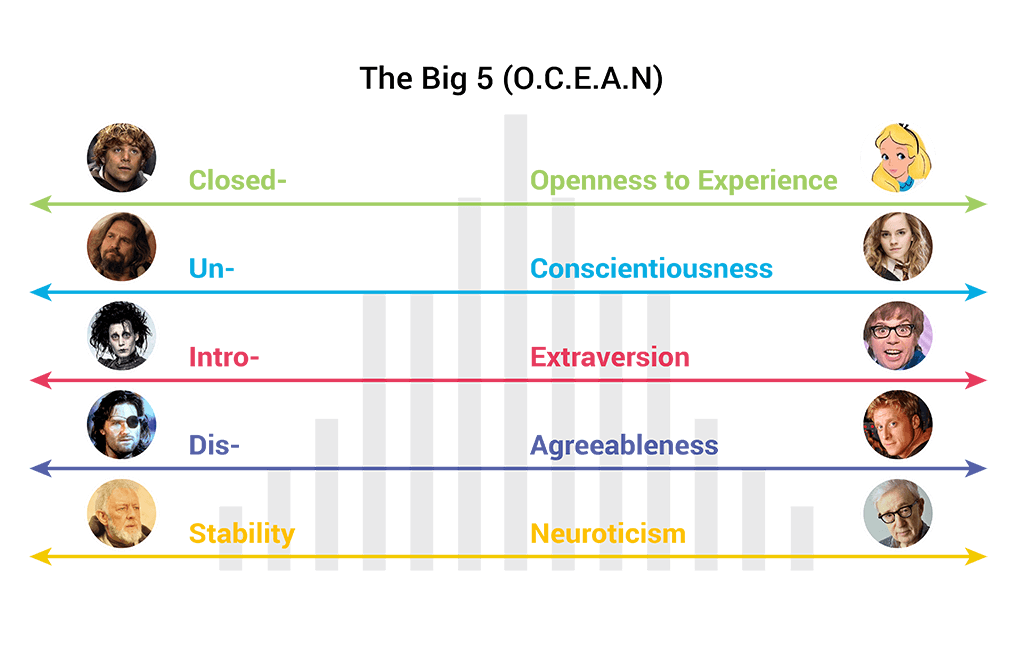

The Big Five

The Big Five puts forward five broad dimensions often used to describe the personalities of people. They are:

- Openness to Experience: inventive and curious or consistent and cautious.

- Conscientiousness: efficient and organized or easy-going and careless.

- Extraversion: outgoing and energetic or timid and reserved.

- Agreeableness: friendly and compassionate or challenging and detached.

- Neuroticism: sensitive and nervous or secure and confident.

The five traits, under the acronym OCEAN, are treated on a spectrum where you can be open or closed to experience, conscientious or unconscientious, and so on.

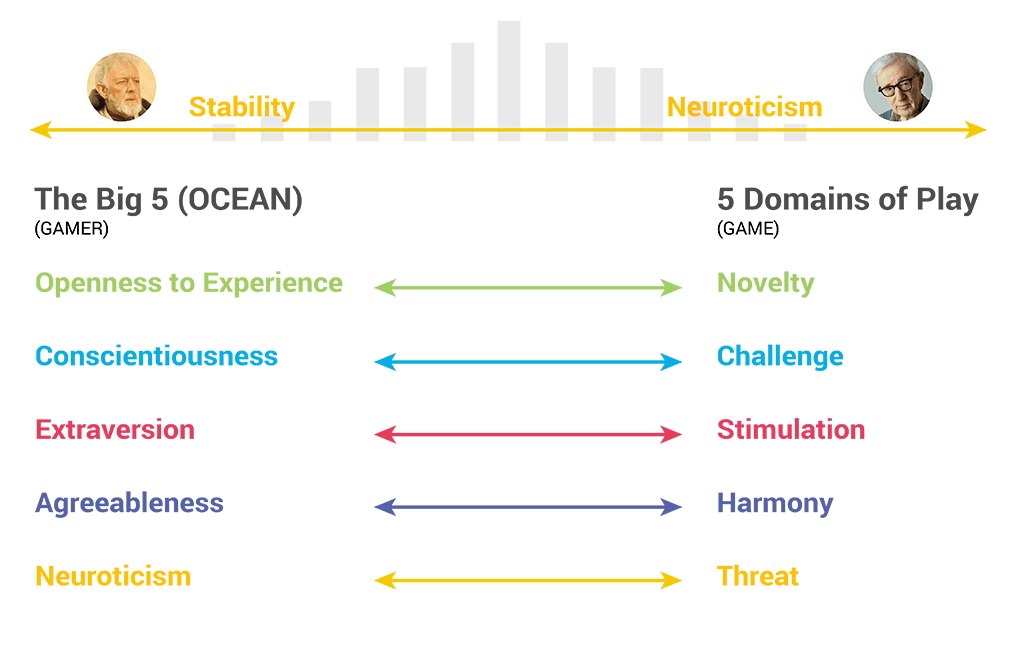

Vandenberghe separated the five traits into gaming-user types and linked them to different video games and their elements. Together, this made the Five Domains of Play. The map Vandenbergh developed for each OCEAN “gamer” and their corresponding game trait is seen below.

For example, a user that is big on neuroticism might enjoy playing video games with a nature of stealth since threats make them nervous.

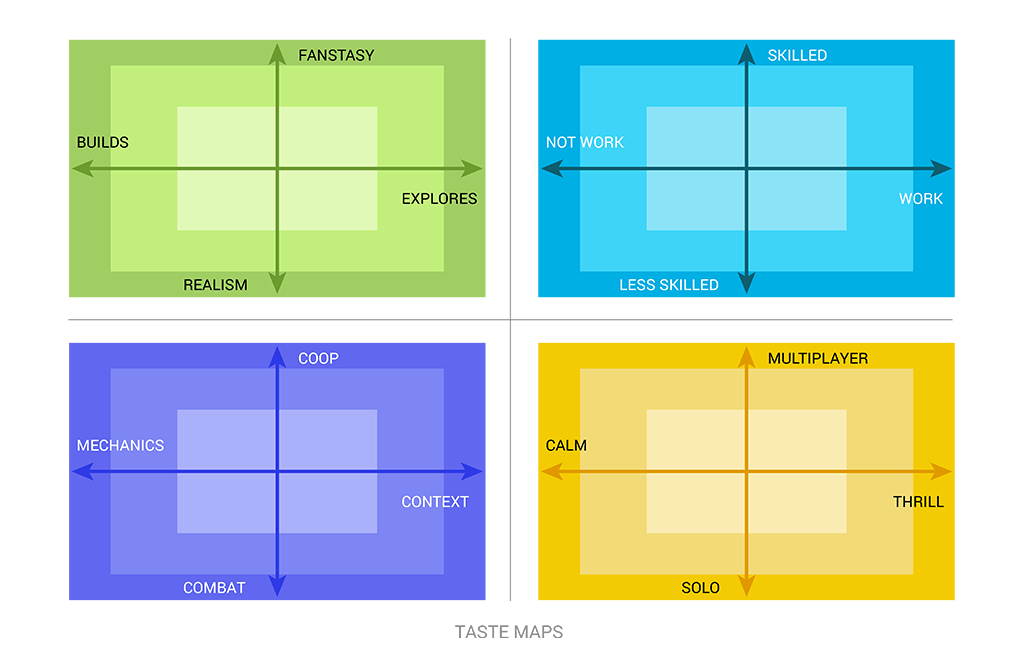

Taste Maps

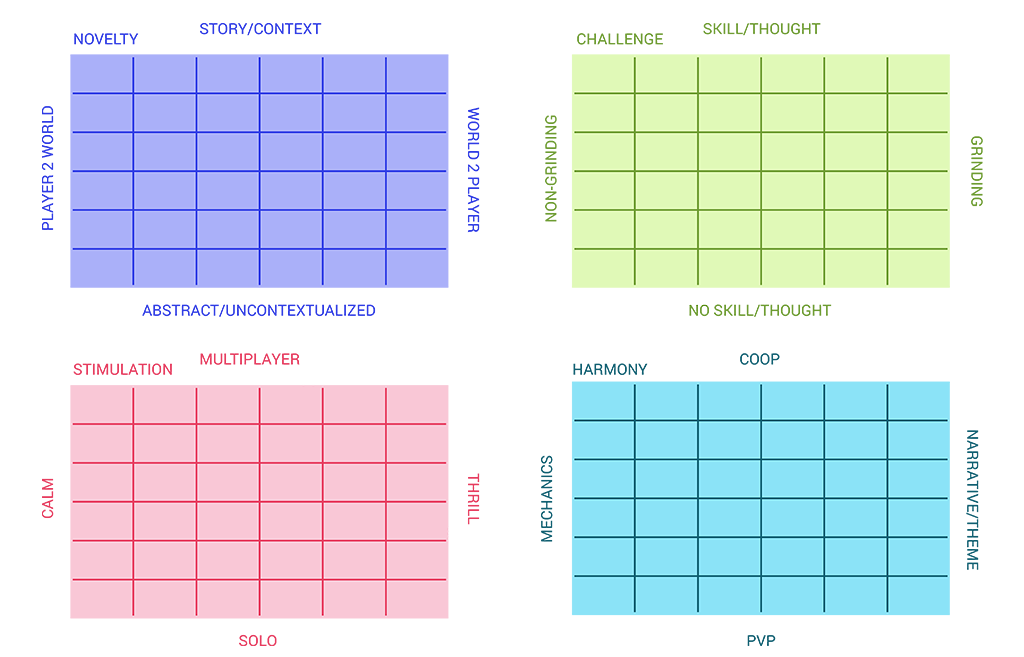

To apply this concept towards a group of players, Vandenberghe developed Taste Maps, a tool that game designers can use to score gamers in the four traits and discover their distinctive preferences. I mention four and not five traits because Vandenberghe did not find sufficient correlation in the Threat element and therefore chose to score players only on Novelty, Challenge, Stimulation, and Harmony.

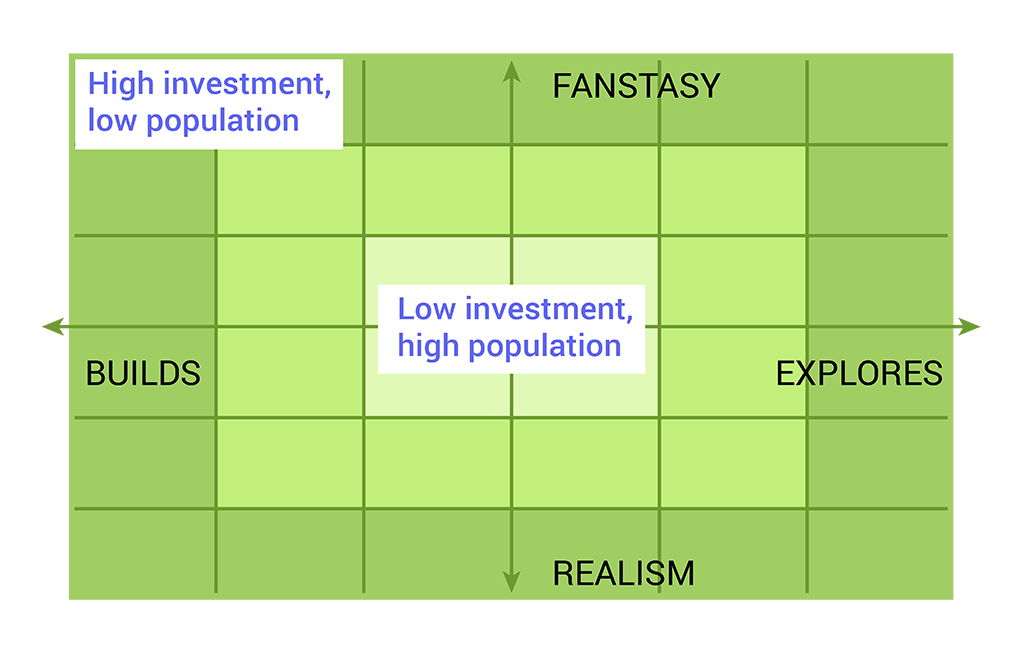

Taste Maps converted users’ scores from the personality tests into unique gamer characteristics. If a person scores high on imagination. one of the Novelty facets. it indicates the individual’s higher value of perception over reality. These were users who would favor games that emphasize fantasy rather than realism.

Vandenberghe’s approach distinguishes the four traits into their respective facets and interprets them into gaming features over 2 spectrums.

- Novelty can be scored on a Fantasy/Realism axis together with a Build/Explore axis.

- Challenge can be scored on a Skilled/Unskilled axis together with a Work/Not Work axis.

- Harmony can be scored on a Coop/Combat axis together with a Mechanics/Context axis.

- Stimulation can be scored on a Multiplayer/Solo axis together with a Calm/Thrill axis.

The color gradient within each map is referred to as investment layers. Depending on where a user is in these layers signifies their degree of interest in that particular game trait. It controls whether or not they will buy a game.

If a gamer is hooked onto thrill but your game centers entirely on the calm spectrum, they will not purchase the game.

On the other hand, people within the middle are generally not invested in the trait so they would not be influenced by whether the game is on the nature of thrill or calm.

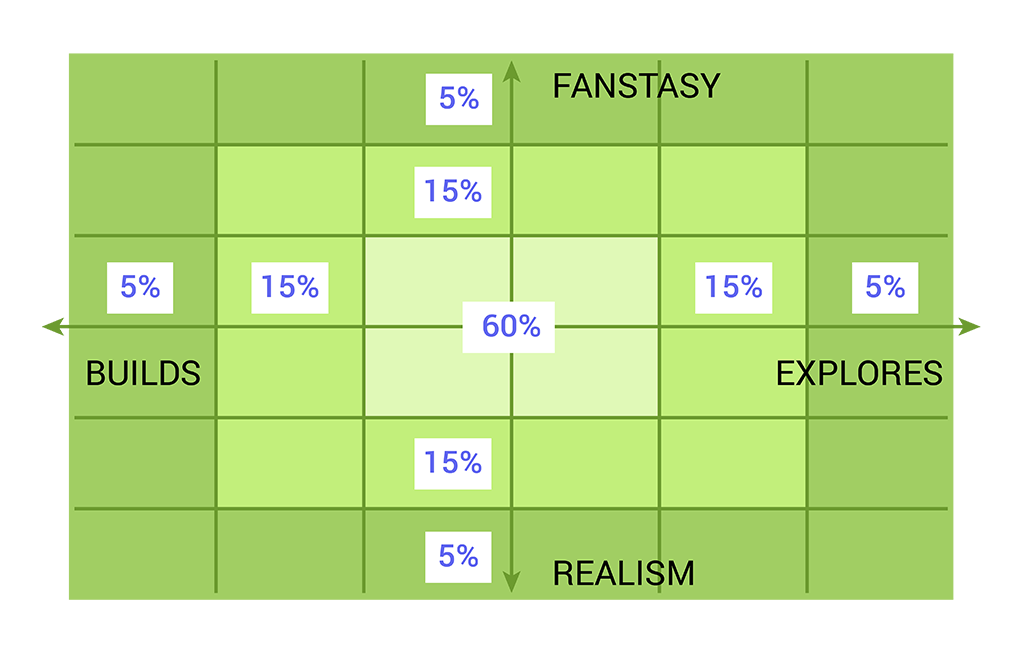

Vandenberghe also considered population distribution along these axes: the majority of people tend to group around the middle whereas the far end of the spectrums – for the super invested – was less dense.

The lightest color of the investment layers, where 60% of people are, lies the bulk of individuals who do not care about the particular trait being examined. The subsequent darker shade incorporates 15% of people that exhibit overall interest in the trait. And the darkest color represents the group that holds a high value for the trait being tested; they comprise of merely 5% of the population distribution.

The individuals on this outermost ring symbolize the genuine and passionate gamers. These are the users who will be devoted to a game that accurately covers the specific trait that they love.

However, at roughly 5% of the population – there are not as many of these enthusiastic gamers.

For that reason, Vandenberghe recommends game designers to balance the population disproportion by acquiring more users from the subsequent darker shade of the investment layer. Designers should focus on obtaining a sizable chunk of the community from the middle and some rare, high-value game enthusiasts from the outermost layers.

Taste Maps in Mobile Free-to-play

Vandenberghe developed the Taste Maps’ axes with a strong AAA and console background during his video game project, For Honor, at Ubisoft. Given my work experience in the casual mobile F2P industry at the time, his axes did not address the games I was developing.

I decided to revisit The Big Five theory and the six facets behind each gamer-type. The goal was to make a transposition that would be applicable to my particular market niche.

In Vandenberghe’s original Taste Maps, he had an axis for Fantasy vs Realism. My changes altered the axis to Story/Context vs Abstract/Uncontextualized. This rendition better accommodated the casual free-to-play sphere, with its variety of abstract games.

The version I developed was not so helpful from the start, though. I revisited the theory numerous times, tested the maps on my own users, and went back to iterating – constantly – until I reached the following maps and axes you see below:

In my mind this is still a work in progress and can, actually should, still be iterated upon.

Conclusion

Remember this key point I made earlier on:

We are guided by our individual tastes when choosing what to begin. We’re guided by universal satisfactions when choosing what to continue.

If you are trying to figure out what type of player will select your game, start by determining their tastes and assuring your game tends to those preferences. Using Vandenberghe’s model, this involves scoring your game along the four Taste Maps – while ensuring that they match your budget.

However, this impact of taste satisfaction will decline over time. The longer you play a game, the less you care about how well it will match your personal preferences.

In these conditions, the Self Determination Theory and PENS model becomes a factor (all addressed in part 1). This will tackle the idea of retaining a long-term player after you have successfully acquired a user to purchase your game.

As SDT and PENS start to affect your user, you need to ask the following:

- What will the player walk away with when they put down the controller?

- How does the game satisfy Competence, Autonomy, and Relatedness?

When these two psychological theories of the Big Five and Self Determination are adjusted into game design frameworks like the Five Domains of Play and PENS, it collectively provides a powerful tool that helps in playtesting interpretation. You acquire knowledge of users’ tendencies testing your game, allowing for better company intercommunications regarding what type of game is being made. As a whole, the tool offers a direct method of game design testing prior to starting development – in the paper prototype stage, even.

These models are, however, not exhaustive. Vandenberghe himself mentions that emotions are not addressed here. Immersyve scientists intentionally excluded sentiments such as fun and instead focused on the building blocks of these emotions. Drives, tricks that always work, are also something not included in these frameworks.

This takes us to the final section of the three-part blog series where I will address the Tower of Want concept, originally introduced by Ethan Levy. It will draw parallels with the Pyramid of Needs (or Hierarchy of Needs) proposed by psychologist Abraham Maslow.